Finding Preacher, Redemption

- Tom Noble

- Nov 25, 2024

- 14 min read

"Now I've been crazy couldn't you tell, I threw stones at the stars, but the whole sky fell. Now I'm covered up in straw, belly up on the table, well I drank and sang, and passed in the stable."

Gregory Alan Isakov, "The Stable Song"

William pushed the barrel of his pistol against the other man's ribs and pulled the trigger. The gun misfired.

What had started as an argument over a girl at a rural Louisiana house party near Ruston had spilled out into the yard, and Preacher - William's nickname since childhood - found himself on the ground taking more of a beating than he was giving. At 22, he had been a scrapper and knew how to fight, but tonight, amid the shouting bystanders he was getting licked. So, he reached for the pistol in his jacket, pressed it into the side of the man whaling on him from above, and pulled the trigger.

When the pistol misfired it made a sound that both the bystanders and his adversary heard. His friends told Preacher later that the man seemed to leap straight into the air. The fight was over. The next day Preacher went out into the woods to test his gun and determine what was wrong with it. It fired perfectly every time. That was in 1935, a year after Bonnie and Clyde had been shot and killed 30 miles west of there, and three years before Preacher met my grandmother, Emma Smith. Now, 44 years later, he was telling me - his 17-year-old grandson - the story.

He and I had been driving together on some errands while they visited us from their home in Crossett, Arkansas. He wasn't proud of what he had done and the story was told with such a degree of gravity and lingering regret that I knew the confession was intended to make an impression on me. My granddad told me it was by the grace of God that the gun did not fire - that only through God's intervention did he not kill the man. He said he thought about it often. Since that day in the car so have I.

My two grandfathers were significant people in my life, and when they talked, when they told stories of their past, I paid attention. That conversation was over 40 years ago, but in the week since the death of William's oldest daughter - my mom - it has been on my mind. Not just that story but all of them. I loved my grandfather with all my heart. Everyone seemed to love William. He was kind, patient and generous. He was also a good story teller. Though he tended towards quiet, when he did speak you got a glimpse of the mischievous nature that endeared him to so many. You just wanted to be around him. I have often been struck by the paradox of the man I knew with the nature of the boy and young man I saw in the stories told by him and others. But I also saw some common threads. I want to reconcile the two. Having now started this, my plan is to write my way through it. I think I will just refer to it all as Finding Preacher.

Tom Noble, February 1, 2020

Finding Preacher (part 2)

"That tall grass grows high and brown, well I dragged you straight in the muddy ground; and you sent me back to where I roam, well I cursed and I cried, but now I know, now I know."

Gregory Alan Isakov, "The Stable Song"

"Tell it, Preacher, tell it!" The men were gathered around the crate, and William was holding court. At the age of nine, he often served as his blind father's lead, and today, like many before, he had brought Ansel to town. William tended to be smaller than the other boys, but what he lacked in size he made up for in tenacity. He had wispy dirty blonde hair and a tendency to bite his tongue when his young temper flared. He didn't know how it had started, but by the age of nine, the little itinerant "preacher" had a following of his father's amused friends.

William was born March 9, 1913, to Ansel and Elizabeth Frazer on their farm between Dubach and Shiloh, Louisiana. He was the sixth child, with one older brother, Coy, ten years his senior, and four older sisters in between: Inez, Addie, Audry and Opel. Two years later his younger brother, Stanford, would be born. Four years after that their mother, Lizzie, would die, leaving the brood of seven children to to be raised by their father, who had been blinded in an accident with dynamite before William was born.

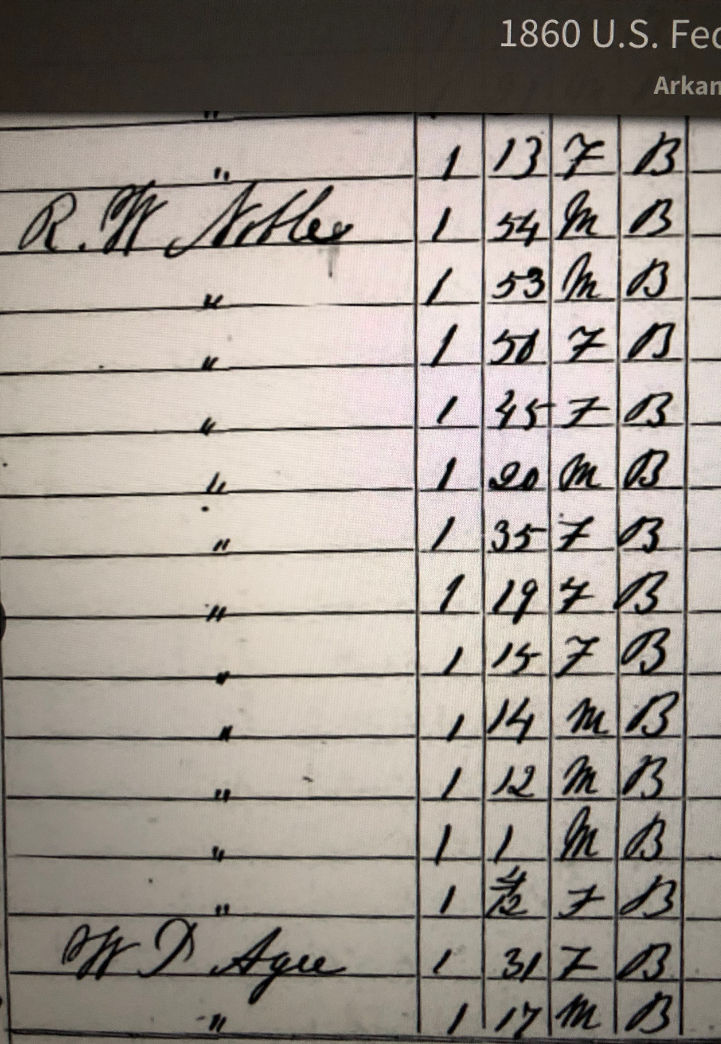

His family had come west to Louisiana a few years after the Civil War when his grandfather, John Frazer, moved them from Georgia. John had owned slaves and fought in the War as a Captain in the 13th Regiment, Georgia Infantry, Jackson's Corp, Army of Northern Virginia. After settling in Louisiana John was elected to be a constable for Union Parish. One evening in December, 1887, while riding home at dusk with his coat pulled up around his face to fend off a cold wind, he was ambushed at a crossroads by two men who mistook him for another and shot him from his horse with their shotgun. With John lying on the ground and dying from his wound, one of the ambushers took aim at his head, fired his gun's second barrel and fled. William's father, Ansel, was only 12 at the time, so William never knew his grandfather apart from the stories that were passed down.

Most of William's childhood was spent without his mother, and under the loose guidance of his four older sisters and brother. Working the farm was difficult and whatever work could not be accomplished by the blind farmer and his three young boys and four girls had to be hired out. The farming community was small, comprised of around 700 people, and even as a child, William was known to most. He had a knack for talking - not just proficiency with words, he was an entertainer. Adult men would set him atop a make-shift platform or a tree stump, and with a little encouragement, William would pour forth a spontaneous speech or sermon, mimicking and mocking what he had seen and heard. He was still a young boy when he earned the nickname Preacher.

Rural Louisiana in the '20's could be rough and crude, especially for a boy growing up without much adult guidance. William, or Preacher, was a scrapper. His stature, coupled with his quick and sharp tongue and a temper that would flare at almost any provocation destined that Preacher had more than his share of fights. On one such occasion he and another boy were fighting, and while kicking and punching in one of Dubach's dirt roads, they rolled up under a parked car. Being somewhat confined, the fight turned nasty and pretty soon Preacher had bitten off the other boy's ear lobe.

Years later, Preacher, was eating with his wife, two adult daughters and their husbands at a cafe in south Arkansas. The two sons-in-law had been joking around with William but noticed his grin disappear and his lips tense. It took a few minutes of prodding, but eventually William quietly explained that the man, who was about his age and that had just been seated in the cafe with his wife, was in fact a man he had known as a boy in Dubach - another boy he had also fought. The sons-in-law didn't think it such a big deal, and glancing back with muffled laughter, confirmed that the unnamed man across the room still had both of his ears; so, Preacher reluctantly explained that while that was true, he knew for a fact that this man across the cafe was missing a nipple.

Tom Noble, March 15, 2020

Finding Preacher (part 3)

"And I ran back to that hollow again, the moon was just a sliver back then; and I ached for my heart like some tin man, when it came oh it beat and it boiled and it rang. Oh it's ringing."

Gregory Alan Isakov, "The Stable Song"

He stepped carefully around the pine cones and broken limbs, his eyes scanning the green canopy above him. At the age of 11 he didn't claim to be the best shot in the Parish, but good enough that he seldom came home from a squirrel hunt empty-handed. He enjoyed being in the woods, alone, taking in the smells and sounds of the forest. He liked the feel of the gun in his hands - it made him feel grown up. Sometimes he imagined himself as his grandfather leading his Georgia regiment through the Virginia woods in battles such as The Wilderness or Cold Harbor.

This day, however, the voices he heard weren't imagined. They weren't far off either. It sounded like two men talking, and he thought he had heard one of the voices before. After pausing, he crept a little closer until he could see three men standing near the river - two white and one black. He recognized one of the white men as belonging to the familiar voice. Preacher instinctively knew this wasn't good. The white men were angry and the black man was mostly quiet and looking at the ground. He thought he saw one of them holding a gun. No longer concerned with stealth, Preacher turned and tried to run, but before he could get far, he tripped over some unseen obstacle in the underbrush and fell.

As he frantically tried to gather himself and make his escape, one of the white men caught up with him, and grabbing him by his shoulder and flailing arm, held him to the ground. Preacher could hardly breathe, and a stifling fear overwhelmed him. As he wrestled against the man's grip and his own growing panic he heard the man say, "Oh, its you, Preacher." After a few seconds under the man's glare, he felt him loosen his grip on his arm. Preacher scrambled to get up as the man chided him with, "Now go on, and get out of here!"

And so he did, running as fast as the low hanging branches and undergrowth would allow until it felt as if his lungs would burst. He had stopped to catch his breath when he heard the gun shot. Again, he started running.

Preacher was too scared to tell anyone, too scared of the man who had recognized him. Scared that people wouldn't believe him. He felt lucky that they hadn't shot him, but he felt guilty too. And so, he bottled it up inside, but it didn't stay there. What he had seen haunted him, and eventually, as a young man, preacher would sometimes carry a pistol - determined not to be found in that position again.

A few summers later, after finishing the eighth grade, Preacher was done - done with Dubach, done with his father's farm. So, deciding to run away, he took one of his father's pigs, sold it, and used some of the money to buy a train ticket to Springhill, where he stayed for a while with his older brother, Coy, and his wife.

A few years passed, and in the midst of the Great Depression, Preacher and his cousin Joe traveled north into southern Arkansas to get work at the Crossett Lumber Company 10 miles on the other side of the Louisiana state line. The logging operation had begun in 1899 and a small company settlement was growing into a small town to house and support the growing labor camp. In the mid '30's Crossett would diversify, opening a paper mill in addition to its logging operation. Preacher signed on as a logger.

Each day the teams would be deposited at the site they were to clear, using two-man crosscut saws - the type that was usually at least six feet long with wooden handles at each end. Two men would stand on opposite sides of the tree, one pulling the blade while the other pushed, then they would reverse the motion until the tree was felled. The key to efficiency depended on the careful syncing of each man with the other to create a rhythm that cut effectively in each direction.

More and more, Preacher was going by his given name of William, despite his growing ability to communicate and connect with people in a way that was still entertaining and disarming. One day the foreman asked William to switch to a different partner. The other man was the strongest and best of the loggers, but he had a problem keeping partners. He wore them out, intentionally. He didn't like many people and most people didn't like him. He could be mean and vindictive, and when he didn't like his partner, and he never did, he would create a drag on the saw blade each time his partner pulled. It was a slight, almost imperceptible resistance, but it would soon wear down the poor recipient of the man's disdain.

The men on the crew soon figured this out. The problem was, that while the logger was universally considered a difficult and mean-spirited pain in the neck, he was also the best in the crew. So the foreman asked William to team up with him in the hope that William's disarming personality would allow him enough time to earn the other man's respect for his own tenacity and physical strength. It also helped that William - still the scrapper - didn't flinch when confronted by a bully. And so, it worked, and William began to build a reputation in his new home.

In 1939, during a trip back to northern Louisiana, William met Emma Smith, and later that same year, they were married. William and Emma moved to Crossett, and set up house in a company-owned rail car that had been modified to serve as a duplex apartment, sharing it with Joe and his new wife. Soon, they would move into a house as the community continued to grow. Over the next five years, William and Emma would have two daughters, and William would begin working in the new paper mill. And life happened.

Tom Noble, April 12, 2020

Finding Preacher, Redemption (part 4)

"Remember when our songs were just like prayers, like gospel hymns that you called in the air. Come down, come down sweet reverence unto my simple house and ring, and ring. "

Gregory Alan Isakov, "The Stable Song"

My enthusiasm for picking tomatoes and beans in the heat and humidity that seemed to never leave my granddads' garden usually lasted about 10 minutes . And the mosquitoes, my constant companions during my summers spent with my grandparents, seemed to like me better than the others. The idea of working the garden appealed to me, but the reality of the work quickly wore thin for an eleven year old from the suburbs. It was here though, that my earliest impressions were made of the work ethic of my two granddads, who shared an acre garden on Dewey Noble's rural home site.

Looking for a distraction, I would often ask them about their childhoods or others in our very large extended families, that from the perspective of a child, seemed to populate the whole county. Living a dozen miles apart in neighboring communities - Crossett and Hamburg - William and Dewey Noble had become friends and shared a mutual respect as well as a garden since the marriage of their two children in 1961.

As a child I looked forward to the summer trips to these small communities where we received the special attention of our extended family, including unhealthy quantities of homemade ice cream, watermelon and firecrackers. I also enjoyed time alone tromping around through the woods with my BB gun, my imagination carrying me off to save encircled battalions in France or homesteads from the Comanches. I loved the smell and the sounds of the forest. What I loved most though, was the predawn fishing trip with my granddad, William.

By many people's standards it probably wasn't much, but it was everything to me. The evening before, he would ask me to help him gather up the fishing tackle and clean out the dull green 14' aluminum Jon Boat. Then we would drive the couple of miles to a bait shop and buy our worms. Back home, we would hitch the boat and trailer to his old green Ford pickup, load the tackle into the bed of the truck and then wash up for dinner. My grandmother was famous for her cooking, at least among the family, so it never disappointed. My granddad would help with the dishes and then I was off to bed on the pallet made for me and my sister at the foot of their bed, the old window unit air conditioner humming above us.

Waking up at 5:00 AM, with the help of my grandmother, to the smell of coffee, bacon, biscuits and eggs rivaled Christmas morning as a time to be anticipated. Once in the truck, we quietly pulled away from the dark street and headed off to Lake Georgia Pacific or the Saline River. It seemed everyone else must still be asleep, but my granddad and I were off on an adventure. I rolled down my window, and mimicking him, let my arm rest within its frame. The smells of the woods, early morning humidity and the nearby paper mill all mingled with the worn smell of the truck's interior. It was dark, my granddad and I sat quietly as the truck and boat trailer rolled out of town, united in purpose, I felt older. I felt important to him.

The time spent on the water was much the same. The smells and the quiet seemed accentuated before the sun fully rose. Words were few and important. And best of all, he let me drive. It was just a Jon Boat and a Mercury 4 HP outboard motor, but my granddad trusted me to drive. He taught me to look out for the stumps that were often hard to see, he taught me how to maneuver the boat slowly up to the perfect place. He taught me how to bait a hook, and wait quietly, patiently. And when my red and white bobber tugged and dipped below the surface sending out ripples on the water, he sprang to help me, enthusiastic and happy for my success. He was always happy for my little successes. He was also the most patient of my childhood teachers.

One of my earliest memories of him was when he let go of my new bicycle as he and Dad taught me how to ride. It was Christmas and I was five. Eventually he would teach me how to drive his "three on the tree" Ford as we drove over to my granddad Noble's house and garden. I was too young to drive in the eyes of the state, but not in the eyes of my granddad.

Watching him I learned how to build and stoke a fire, paint a house, feed the ducks at the pond down the street, and walk quietly through the woods. William was the one who, while visiting from Arkansas in February 1969, drove me to my first grade girlfriend's house so I could give her a red heart-shaped box of chocolates like my dad had done for my mom earlier that day. When my girlfriend, Cheryl, unexpectedly reached to hug me and kiss my cheek as we stood on her porch, I wrenched around to see if he, still sitting in the car, had seen it. Back in the car, I quizzed my granddad about the incident, but to my relief he said he was looking off the other way and must have missed it. So he said, and spared his six year old grandson the embarrassment.

Over time I realized the other things my granddad, Preacher, taught me. It is not lost on me that my granddad was the grandson of a slave owner - a man who enslaved other human beings, yet he showed his own grandson how to respect people and embrace hard work. He never knew his grandfathers but he loved his six grandchildren with patience and devotion. His childhood was difficult and sometimes harsh, but he raised his two daughters such that their fond devotion and love for him is one of my most defining memories of our family. He respected and loved his elderly mother-in-law and my grandmother's brothers and sisters, his nieces and nephews. Family was important.

I paid attention and the most significant thing I saw when I looked at my granddad's life and his transformation to a father respected and loved by his daughters, and the patient grandfather of six, I saw God's hand and God's grace. I saw redemption - redemption from a legacy that he would not pass on to his grandson. Now that I am a grandfather myself, I see a man that I wish my kids and grandsons could have known. He lived long enough to see my first daughter born, but died when she was three. And while my two girls never knew Preacher, I hope that they sometimes catch a glimpse of him.

When I was young, I wanted the world to know who I was. Now, knowing myself, I am more interested in grace, forgiveness and knowing who God is - something else I learned from my granddad, Preacher.

"Ring like crazy, ring like hell Turn me back into that wild haired gale Ring like silver, ring like gold Turn these diamonds straight back into coal."

Gregory Alan Isakov, "The Stable Song"

Tom Noble, April 29, 2020

Comments